Cultural Correlation and Conflation

If you look beyond religion, and approach being Jewish also as a cultural and racial identity (which most do), then there’s a correlation between being Jewish and being Chinese. If you see a Han Chinese person on the street, all you see is their race. You don’t necessarily know if that person is a citizen of the People’s Republic of China. And even if they are, you cannot equate them with the actions of Xi Jinping and the Chinese ruling classes. Likewise being Jewish is not the same as being Israeli, which is also not the same as being Bibi Netanyahu. Yet in both cases it’s extremely common for people to conflate race, nationality and government into one amorphous blob.

Where the analogy ends of course is that you don’t see people calling for the annihilation of all Han Chinese people based on the actions of a government that corresponds to their race. So yeah howzabout we don’t call for the annihilation of anyone as an appropriate response to any government’s treatment of a minority or neighbour. Let’s debate the opposing acts of aggression which led us to this point; the actions of governments or militia purporting to act in our name; and the ways in which we’re all individually complicit or not. But can we at least all agree on the bit about annihilation?

It’s uneasy times for all of us. But for just one day, I forgot these thoughts as I celebrated the Jewish new year with a lovely group of close friends in Shanghai. And with one of their 9-year-old daughters having hand-made challah like this, how could we not have a little hope in our hearts? 🌈 Here’s wishing everyone שָׁנָה טוֹבָה (Shanah Tovah), and I hope we can all find something to celebrate this year. 🙏

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

Cultural Appropriation in China?

Living in China is the best way to ensure that your life is spent constantly tying yourself up into intellectual knots. My ‘quandary of the week’ this week was about cultural appropriation.

Let me set the scene. Cultural appropriation is a situation where someone from a dominant position in society inappropriately adopts a tradition from someone in a less dominant position. And we all know what this means through a European/American lens, a white person there is clearly trespassing on someone else’s culture if they inappropriately wear afro wigs, Sikh turbans or Native American headdresses, for example. But I can potentially see plenty of grey areas to this too. For example, is it cultural appropriation when someone who speaks with an accent from a more affluent part of a country adopts a regional accent from elsewhere? Or what about when a white person becomes a fan of hip hop - with its specific African American historical context - and then starts wearing clothes associated with that style? I guess the key aspect is in what kind of adoption is deemed ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’, and we can all see how these definitions can change as society progresses… or regresses.

In China, there’s an academic term for cultural appropriation, it’s 文化挪用 [wénhuà nuóyòng]. This is way above my conversational pay grade, so I have no idea how many people even know this oblique reference. I asked a few Mainlanders, Hongkongers and Taiwanese people in my circle, and even the ones who knew it didn’t really think it applied to China. So although the dominant culture here is the Han, there’s no reckoning that a Chinese Han person wearing clothes from a minority ethnicity could be deemed intrinsically inappropriate or offensive.

It is common practice here for Han Chinese tourists to take photos of themselves in local costumes when they visit areas populated by ethnic minorities. The people I asked told me that they wouldn’t associate this with the concept of cultural appropriation, and that the behaviour of the wearer was based on respectful curiosity, thousands of years of cultural intermingling, and a genuine appreciation of the aesthetic beauty of the garments. When I asked about what the minority ethnicities themselves might think about this, for most people it was the first time they had thought about it in that way. The ones who answered did so confidently, saying that the ethnic minorities aren’t offended. At the very worst, it was a kind of Chinese ‘cosplay’ done out of reverence rather than mockery.

It’s a tricky one to figure out, because China exists outside the specific history of colonialism and slavery that typifies the way we look at cultural appropriation in Europe and the Americas. So it’s inaccurate to do a like-for-like comparison, and I try not to impose my own cultural baggage onto anyone else. What muddies the waters further is that the government in China has made a point of pushing the narrative of 和谐 [‘harmony’] between Han Chinese and the other 55 officially-recognised ethnicities in China, so anything that speaks against this is seen as political sacrilege. So there’s zero chance that I could witness an open debate about this, even if my Mandarin skills were up to it. Which they most definitely aren’t.

Now we’re getting to my quandary of the week. We had been invited to a traditional Chinese wedding, which in itself is quite rare in Shanghai. Most people these days have modern weddings which would be recognisable to anyone around the world. But this was very different, the bridal party were all dressed in amazing traditional attire and performed a variety of ceremonies that harked back to rites of old. So in a way, the wedding was a sort of traditional Chinese ‘cosplay’, where our fellow Chinese guests were dazzled to a rare experience in just the same way as we were. With this in mind, we had been told that the bride would appreciate if we respected the occasion, and were encouraged to wear formal Chinese attire.

I’ve lived in China for almost a decade, and have made a point of never wearing anything traditionally ‘Chinese’, lest it be misconstrued as a disrespect to my host country. Yet we were convinced that this was clearly a case of ‘appropriateness’, so we bit the bullet and got some Chinese-style suits made. That would have been the end of this anecdote, were it not for what happened on the night of the wedding. Luckily we arrived early, so we were able to see guests as they trickled into the venue. And it soon became clear that there had been a massive miscommunication. None of the other guests were wearing anything approaching traditional Chinese clothing. In fact, many of them appeared to be wearing clothes that they had worn earlier that day. We’re talking jeans, even sweatpants. Meanwhile I was sat there looking like a poor imitation of Sun Yat-Sen.

We solved the issue by quickly removing our jackets, and we were able to blend in with the other guests a little easier. But not before we were noticed by the bride and groom themselves, who both greeted us with straight faces. One day I would like to get them drunk and ask them what they truly thought about our ridiculous appearance. I hope it will become a funny family anecdote that they can tell their kids in the future. But until then I will add this to the countless other embarrassments that seem to have constituted my life up till today.

If there is any moral to this story, let it be this. The definition of cultural appropriation can indeed change over time, perhaps even in China. Sometimes it takes a generation, and sometimes it literally takes FIVE MINUTES OF TESTICLE-SHRINKING TORTURE. So when in doubt, don’t be an arse, and wear your regular clothes.

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

Imperial Eccentricity

Happy Thanksgiving from Shanghai to everyone who celebrates it!

Clearly the thing for which I’m most grateful is my American husband, because our marriage gives me the excuse to have a massive meal tonight, with all the trimmings. 🦃🇺🇸

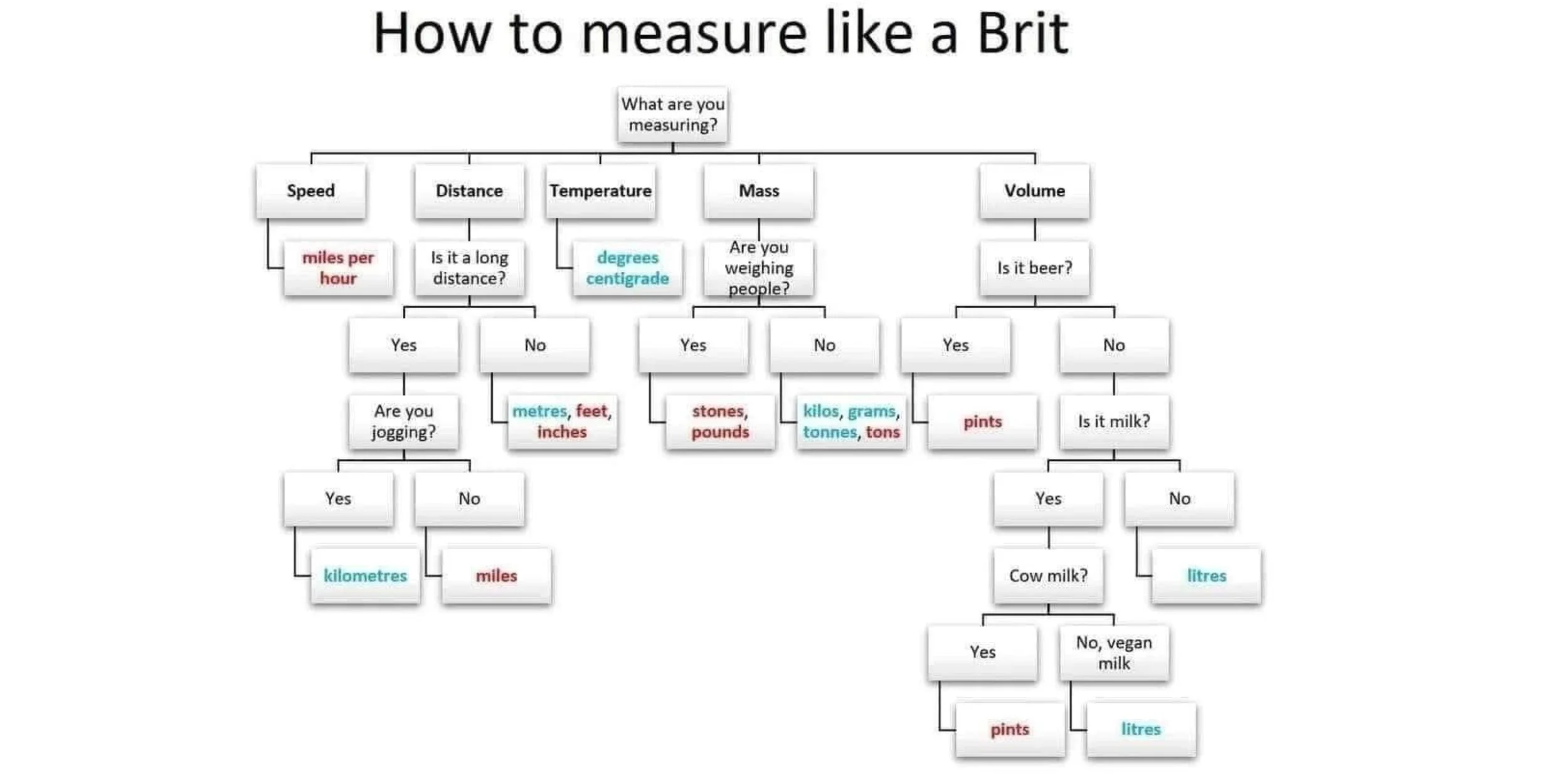

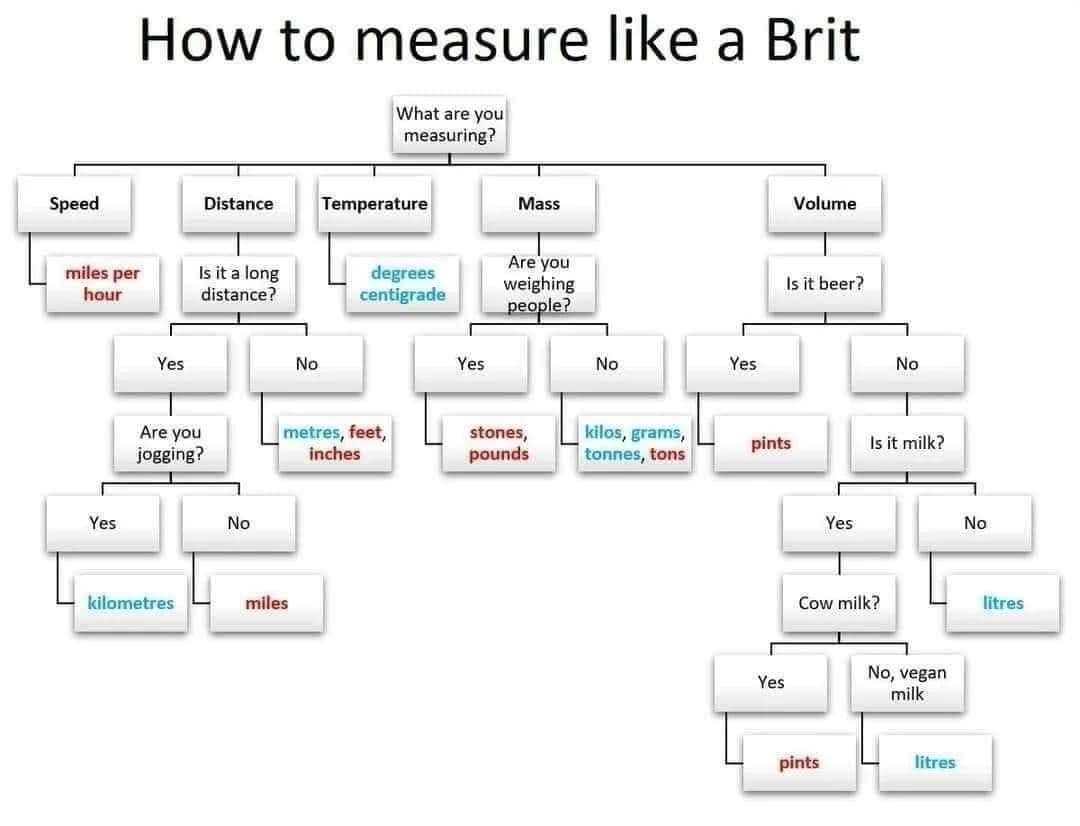

In the spirit of our transatlantic union, I’m posting this graphic which I found online. To those Americans who are proud of their eccentric adherence to imperial measurements… this Thanksgiving, just be grateful you’re not as eccentric as the Brits. 🤪🇬🇧

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

China as an Overbearing Parent

A few residential compounds have started to open up in Shanghai, and there’s hope that this represents the beginning of the end of this harsh city lockdown. In our case, one of our neighbours has been entrusted with the key to the lock on our gate, and she has started to leave it unlocked at random times of the day. We have no idea how this seemingly arbitrary decision got made, or by whom. But we’re in no mood to enquire; we just want to take a walk around the block.

There’s no thought of celebrating yet, while so many of our friends remain behind closed doors. Besides, the streets remain empty; shops remain closed; and everyone is nervous that the slightest uptick in positive COVID cases may put us all back to square one. And square one is where most of the city still languishes, just by luck of the lockdown lottery.

The two questions we’ve recently been asked the most are: 1) Why is China doing this? And 2) Why would anyone now wish to remain in Shanghai? To answer the first question, I would need to explain how China works, and only an idiot would try to suggest one unifying theory. So here’s mine.

China seriously cares for its people. That’s a fact. But it cares for them as a 1.4 billion collective, not as 1.4 billion individuals. China is an overbearing parent looking after their single child. They only want the best for it. They let it play, albeit under very tight supervision. They tell it what to do, and scold it when it steps out of line. No nuance; no negotiation. Does an overbearing parent always know what’s best for their child? And when other parents offer them unsolicited advice or criticism, does an overbearing parent get offended?

It’s an only child: the child is one; the child is indivisible. The parent does not need to understand each of the 1.4 billion individual cells that constitutes their child. Why would the concept of a cell even occur to them? The same goes for certain clusters of cells, certain organs and systems. If the parent feels that they’re keeping the child in general good health, does it matter to them what a tonsil does? Or a gallbladder, or an endocrine system? So long as China feels that it’s keeping 1.4 billion people in indivisible harmony, then what do the needs of a specific minority group matter? Or a city? Or a functioning system of public discourse? There’s a fundamental disconnect between the pure parental love of the child, and the complicated tangle of biology beneath its skin.

Most people outside of China (and some of us within!) just view the situation from the perspective of the cell. But in making this entirely accurate assessment, we’re also missing half the picture. The cells are also the child is also the cells. So an average individual in China feels both loved and unloved at the same time. Hugged too tight, and heedlessly ignored. Schrödinger was late to the game, the Chinese have understood the paradox of yin and yang for centuries. Today’s China is a mixture of Confucius, Han Feizi and Mao. While from the outside, we only see it through the prism of Beckett, Kafka, and Orwell.

So having lived through China’s recent metaphorical heart attack in Shanghai, we need to turn to the second question: why would anyone who has a choice decide to remain in China?

This is a question that every person must answer individually, so I can only speak for myself. My answer is that cross-cultural experience isn’t just about traveling the world comparing delicious desserts. You can learn more from panic attacks than you can from patisseries. Would I prefer to be eating pear tarts in Paris right now? Oui. But do I also value being able to think like I do, and view the world like I do? And at exactly what point does that privilege come at a price that I’m no longer willing to pay?

Making the decision to stay or leave one place or another is always a question of principle and practicality. When the effects of COVID-19 were ravaging your city, did you break your lease, quit your job, cut ties with your community, and relocate? It would be understandable if you had, but just as understandable if you hadn’t. We won’t stay in China forever; at some point the winds of fate that blew us here will also blow us away. Until then, we’re going to continue making the most out of our time in this land of paradox.

For the Instagram version, see here.

For the Facebook version, see here.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

The Sage Kings of Karaoke

There’s a reason why karaoke is so popular in China and other East Asian societies with a Confucian heritage: it’s an important catalyst for group social harmony.

The Sage Kings of ancient China used the rites of music to help bond their subjects together. It’s no coincidence that the Chinese Communist Party emphasised the use of patriotic songs to instill doctrinal fervour. And today, many Chinese corporations still use company songs, alongside collective exercise routines, to inspire loyalty.

Today's compilation episode from Season 1 of Mosaic of China is all about the podcast guests’ favourite songs to sing at “KTV”, the Chinese version of karaoke. Out of all the questions asked to guests on the show, this one elicited the biggest array of emotions: from joy and pride, to embarrassment and… sheer terror.

It’s a shame that group social harmony doesn’t always guarantee group *vocal* harmony. But since no-one really cares about that… what would be *your* go-to song to sing at karaoke?

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

For the Mosaic of China version, see here.

A Fundamental Aspect of Life in China

The Coronavirus has brought China’s full-speed economy temporarily screeching to a halt. But it hasn’t changed one fundamental aspect of modern life in China:

The adaptability of its people.

For the LinkedIn version, see here.

My Left-Handed ‘Handicap’

In my first week of living in rural Japan back in 1999, I was called ‘handicapped’ for attempting to write Japanese characters with my left hand. Some 20 years on, I now find myself in Shanghai, writing up my Chinese revision notes with the same handicap.

Out of all the things that still fascinate me about living in Asia, the one thing about which I would write a thesis is the treatment of left-handedness in Japan and China.